The Northern Hemisphere school year is beginning, yet there is no end in sight to the COVID-19 pandemic. The short-term impact on students, teachers and parents is substantial and quite visible. The long-term impact on students and society will be significant but is quite uncertain.

To bring attention to the potential long-term effects and to build the case for taking additional mitigation actions, a group of World Bank economists estimated the potential long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic quantitatively. They published their analysis in a report in May but have been promoting the findings more recently. In a summary posted on Brookings at the end of July they write:

The students currently in school stand to lose $10 trillion in labor earnings over their work life. To get a sense of the magnitude, this sum is one-tenth of global GDP, or half of the annual economic output of the United States, or twice the global annual public expenditure on primary and secondary education.

The report's framing around their $10-trillion estimate is attention-grabbing but mostly unhelpful--it's not tied to actionable policy options and the uncertainty involved is huge and not sufficiently characterized. Beyond the top-line number, the report identifies several negative short-term and long-term effects the pandemic will have on students around the world.

In applying the standard models for assessing the returns of education to the shock of the pandemic, the report also casts some of the major assumptions of such models in a new light. These assumptions are deeply embedded in policy thinking about education. They likely also appear in your own views about education at times. But these assumptions are often inappropriate and can be quite limiting. I will share a bit more about the report and then return to this point below.

The report identifies three main impacts of school closures:

- Increased dropout rates

- Missed learning for the time school is closed

- Increased learning loss from the longer period out of school

The increased dropout rates stand out as the most concerning and non-obvious effect because students who drop out miss the schooling they would have received during the closures (like all students) and miss the subsequent period they would have remained in school if there wasn't the disruption.

The other two effects are notable, but they also bring to light deeply ingrained assumptions about how education translates to learning and how learning translates to higher earnings.

The report's main model is built around a metric called learning-adjusted years of schooling (LAYS). LAYS is a country-level measure of the number of years of schooling that students in that country complete on average, adjusted by a quality factor for that country. To estimate the impact of school disruptions, the report calculates the pandemic's effect on LAYS. It then translates that into a change in earnings using returns to education estimated elsewhere.

The LAYS metric was developed and published in 2018 by several other World Bank economists to replace the metric previously used for cross-country comparisons, which only considered years of schooling without any quality adjustment. Except in its use of the s newer quality-adjusted metric, the report's approach using years of schooling as the primary input variable has been the standard methodology in labor economics for nearly 50 years.

The origin of using years of schooling to explain variation in earnings was the ground-breaking empirical work of Jacob Mincer. Mincer was a professor at Columbia, part of the Chicago School of Economics and considered by many to be the father of modern labor economics (the Society of Labor Economics gave Mincer the organization's first-ever career achievement award in 2004 and subsequently named the award the Mincer Award).

Mincer first formulated what came to be known as the Mincer equations in his 1974 book Schooling, Experience and Earnings. The equations predicted earnings as a function of years of schooling and years of work experience using data from the 1950 and 1960 US Censuses. A 2003 paper summarized the impact of this work on the profession:

Jacob Mincer's model of earnings (1974) is a cornerstone of empirical economics. It is the framework used to estimate returns to schooling, returns to schooling quality, and to measure the impact of work experience on male-female wage gaps. It is the basis for economic studies of education in developing countries and has been estimated using data from a variety of countries and time periods. Recent studies in economic growth use the Mincer model to analyze the relationship between growth and average schooling levels across countries.

The new LAYS measure was only formally proposed and published by the World Bank in September 2018. That the simple years metric survived so long is remarkable. It is even more so that in introducing the new measure, the author's needed to spend significant time motivating for the change by justifying a claim that should be obvious to even the most naive observer of education: "schooling is not the same as learning".

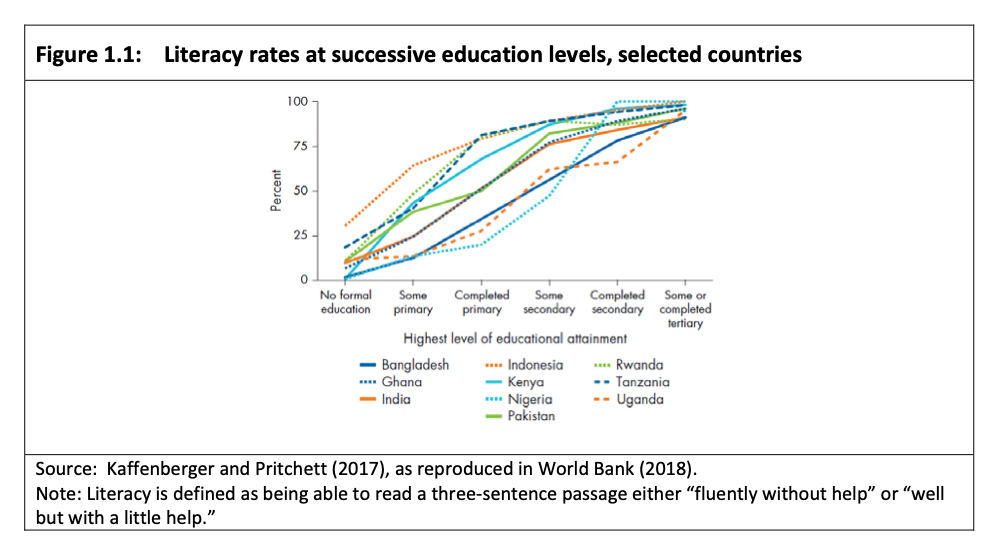

Not surprisingly, they show that learning varies significantly across countries for the same amount of schooling:

In Nigeria, for example, 19 percent of young adults who have completed only primary education are able to read; by contrast, 80 percent of Tanzanians in the same category are literate. At any completed level of education, adults in some countries have learned much more than adults in other countries. (See Figure 1.1. - reproduced below)

As you might expect, these differences in learning also correlate with notable differences in people's lives. The World Bank reviewed studies that looked at the impact of learning controlled for years of schooling, which found higher learning levels are correlated with higher individual earnings, fewer deaths in childbirth, and social mobility beyond that explained by years of schooling.

Adjusting years of schooling for learning is much better than the previous metric, which completely ignored quality. But as the use in this pandemic analysis shows, it still puts most of the attention on years of schooling as the primary lever under policy makers' control. That is in part because the quality factor is calculated from comparative performance on international tests. This would be a bit like creating a quality factor to compare years of schooling in two US schools by adjusting for the average SAT scores of their students. The test scores are in part related to the quality of schooling, but the relationship between variables a teacher or school control and the test scores is a black box. As a result, the quality part of the equation is not very actionable. In contrast, the years of schooling part is directly actionable, and, in this model (and the previous reining model), more years of school equals higher earnings.

For cross-country comparisons of schooling, such a model may be appropriate. There is an incredible amount of variation in school systems within countries, so any holistic comparison is necessarily going to involve a high degree of abstraction. Moreover, getting comparable data across an extensive set of countries is difficult. The required data (years of schooling and the test score information) can be collected regularly and consistently.

But in other contexts, this model is less suitable. In particular, in addition to focusing attention on years of schooling as a major policy lever, the model embeds several strong assumptions that contribute to a clock-time mindset that is pervasive in our education system. Two particular assumptions stand out:

- Time (adjusted for quality) is the only thing that matters. In this model, finishing college in three years would predict a lower earnings premium than finishing in the standard four.

- All time in school is the same: In this model, only the total number of years of schooling matters. It predicts that a year of elementary school has the same impact on lifetime earnings as a year of high school. Missing a year in the middle is the same as leaving school a year earlier.

This model is not designed to predict earnings for an individual person. But on the individual level, everyday experience tells us that these simplifying assumptions obviously break down. Not every class or school year has the same impact. But, with the help of models like these, this kind of thinking is embedded in national policy thinking and, in turn, percolates to district- and school-level decision making.

This model is both a product of and a contributor to our cultural view of education that incorrectly privileges the passage of time as a sign of progress. In Dark Horse, Ogi Ogas and Todd Rose capture the absurdity of basing education on what they call "standardized time":

In the United States, most undergraduate programs require exactly four years (or 120 credit hours) to get a bachelor’s degree, whether you are majoring in marketing or marine biology or Mandarin, whether you are attending a large public land-grant university or a small private liberal arts college, whether you are taught by Nobel Prize–winning professors or distracted teaching assistants—whether you learn fast or slow.

Using the credit hour system, most colleges discourage and even erect barriers to completing bachelor's degrees in fewer than four years. In Hire Education: Mastery, Modularization and the Workforce Revolution, Michelle R. Weise and Clayton Christensen explain the credit hour's origin, adding even more to the absurdity:

Institutions of higher learning do everything possible to measure fixed seat time by relying heavily on the Carnegie unit, or the credit hour. Unfortunately, however, “the credit hour was never intended to be a measure of, or proxy for student learning.” As Amy Laitinen, deputy director of the New America Foundation, wrote, “Andrew Carnegie set out to fix a problem that had nothing to do with high school courses: the lack of pensions for college professors.” What began as a way of accessing Carnegie’s pension program quickly became the building block of every college course and degree program as well as a signaling mechanism of educational quality. Colleges and society now attribute a bachelor’s degree to the accumulation of 120 hours of course work. This numerical output has strangely become a proxy for quality even though there are no standard assessments tied to measuring this time- based learning—in other words, there is no assurance that a student has accomplished anything meaningful in this time.

In our traditional education system, everything can be captured by how much time has passed. If you ask a student how far they are in their degree, they will likely respond without hesitation using a reference to time: "I'm a junior" or "I have one year left."

This clock-time mindset pervades primary and secondary education, too, in myriad ways, for instance:

- In normal school years, schools are subject to strict laws on how many days must be included in a school year and how many hours must be in a school day but not similarly strict laws on outcomes or quality.

- For students in primary and secondary school, attendance is treated much more seriously than performance.

Time is not irrelevant. Research on memory shows that practicing recalling something over time is essential to long-term memory formation. Socialization also depends in part on the passage of time. But the current system dramatically overemphasizes the importance of time. That is a great mistake.

This same time-based mindset often also carries over to the workplace: seniority and promotions often depend on years of experience in a given role. Job postings focus on years of experience as though all years are the same or close enough. In hiring decisions, firms or individual hiring managers may use their own heuristics to make adjustments: perhaps two years as an engineer at Facebook is considered roughly equivalent to three years at a less well-known company. But time is one of the most prominent requirements and usually the only quantified ones for employees.

These rough assumptions may be OK for making broad international comparisons over time, but they provide terrible guidance for our own personal education decisions. Unfortunately, our education system and schools are built more or less around these assumptions being true.

But what if these assumptions aren't correct? Then this clock-time view of education would be misguided.

I expect that just making these assumptions explicit will make you suspicious of them. We intuitively know that things can be learned faster or slower. We know that it wouldn't make much sense to expect lower earnings for someone who finished college in three years instead of four.

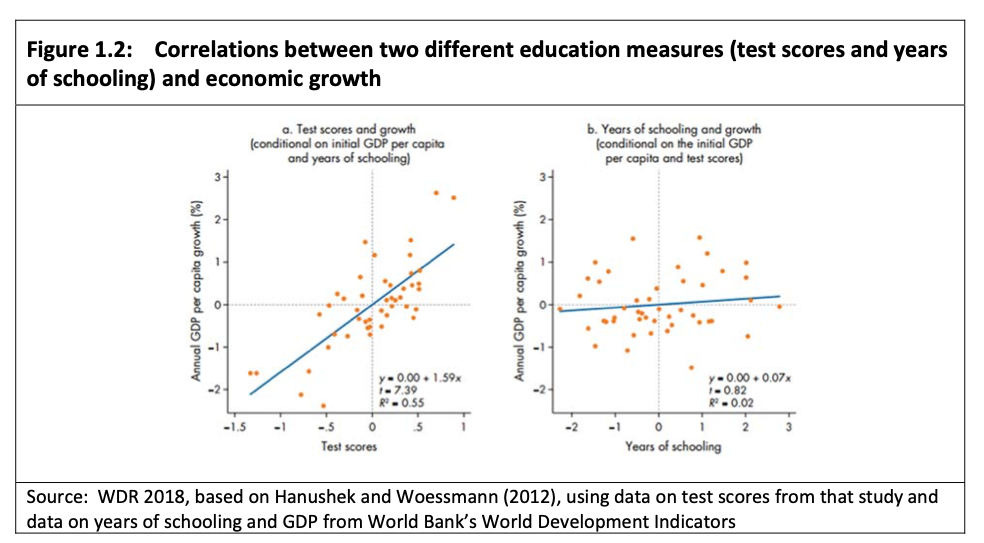

The 2018 paper establishing the quality adjustment includes evidence that the focus on years of schooling may be misplaced and that adjusting for quality does not go far enough. They cite a study on the relationship between schooling and economic growth that found that what mattered was students' abilities as measured by test scores only not years of schooling and test scores:

While the relationship between test scores and growth is strong even after controlling for the years of schooling completed, years of schooling do not predict growth once test scores are taken into account, or they become only marginally significant” (WDR 2018, citing Hanushek and Woessmann 2012; see Figure 1.2 - reproduced below).

The chart on the left of Figure 1.2 shows a strong relationship between test scores and GDP per capita when controlling for years of schooling. The chart on the right shows that the relationship between years of schooling and GDP per capita is not statistically significant when controlling for test scores.

The assumption that all years are the same is equally suspect. The 2018 paper authors come to the conclusion that "learning trajectories have a plausibly local linear trend, especially across the grades that we are interested in." By grades they are interested in, they restrict their focus to grades 6-10. To reach this conclusion, they go through a tortured discussion of data that clearly shows an S-curve, non-linear trend over a wider range of grades.

For students and workers, repeated interaction with a time-based education system encourages a rate-limiting mindset. There is no incentive to learn the material faster--you can't accelerate the course, and you can't accelerate your overall degree completion. Moreover, as long as a student gets through the school year and passes their classes (which may or may not require competence in or mastery of the subject), they will move on regardless. So what's the point of trying too hard? Without any incentive to try to learn more quickly and efficiently, students don't even learn what their potential is to do so. This is a bit like teaching someone to drive a manual transmission car but not showing them that they can shift out of first gear.

Some education innovators are taking a different approach. In the last decade, a number of colleges and universities, including Southern New Hampshire University and the University of Wisconsin have launched competency-based education (CBE) degree programs. CBE programs take advantage of the increased flexibility and personalization capabilities of modern online learning platforms. Students can proceed through the material at their own pace, with completion of a course based on proven mastery of the material.

Innovation in this direction by other players has been limited: traditional colleges and universities are organized around clock time and the credit hour, and they don't show signs of changing. But there is no reason for parents, students, teachers or school administrators to accept a simple clock time mindset for education as they navigate the pandemic and beyond.

A crisis like the current pandemic will cause many direct and indirect changes to how we live and work. It may also cause us to see our former circumstances with a new perspective. Perhaps navigating the shock to our system caused by the pandemic will help us see our reliance on clock time in a new light. We could all benefit by switching to a different way of conceptualizing progress in education.